Roger Mudd

Roger Mudd | |

|---|---|

Mudd at a taping of Christmas in Washington in 1982 | |

| Born | Roger Harrison Mudd February 9, 1928 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | March 9, 2021 (aged 93) McLean, Virginia, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1953–2021 |

| Spouse |

E. J. Spears

(m. 1957; died 2011) |

| Children | 4 |

Roger Harrison Mudd[1] (February 9, 1928 – March 9, 2021) was an American broadcast journalist who was a correspondent and anchor for CBS News and NBC News. He also worked as the primary anchor for The History Channel. Previously, Mudd was weekend and weekday substitute anchor for the CBS Evening News, the co-anchor of the weekday NBC Nightly News, and the host of the NBC-TV Meet the Press and American Almanac TV programs. Mudd was the recipient of the Peabody Award, the Joan Shorenstein Award for Distinguished Washington Reporting,[2] and five Emmy Awards.[3]

Early life and career

[edit]Mudd was born in Washington, D.C.[4] His father, a World War I veteran, John Kostka Dominic Mudd, was the son of a tobacco farmer and worked as a map maker for the United States Geological Survey. His mother, Irma Iris Harrison, was the daughter of a farmer and was a nurse and lieutenant in the United States Army Nurse Corps serving in the physiotherapy ward in the Walter Reed Hospital, where she met Roger's father.[5] Roger attended DC Public Schools and graduated from Wilson High School in 1945.[3]

Mudd earned a Bachelor of Arts in History from Washington and Lee University, where one of his classmates was author Tom Wolfe, in 1950, and a Master of Arts in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1953.[6][7] Mudd was a member of Delta Tau Delta international fraternity.[8] He was initiated as an alumnus member of Omicron Delta Kappa at Washington and Lee in 1966.[9]

Mudd began his journalism career in Richmond, Virginia, as a reporter for The Richmond News Leader and for radio station WRNL.[2] At the News Leader, he worked at the rewrite desk during spring 1953 and became a summer replacement on June 15 that year.[10] The News Leader ran its first story with a Mudd byline on June 19, 1953.[11]

At WRNL radio, Mudd presented the daily noon newscast. In his memoir The Place to Be, Mudd[12] describes an incident from his first day at WRNL in which he laughed hysterically on-air after mangling a news item about the declining health of Pope Pius XII, mispronouncing his name as "Pipe Poeus". Because Mudd failed to silence his microphone properly, an engineer intervened.[13] WRNL later gave Mudd his own daily broadcast, Virginia Headlines.[14] In the fall of 1954, Mudd enrolled in the University of Richmond School of Law, but dropped out after one semester.[15]

WTOP News

[edit]

In the late 1950s, Mudd moved home to Washington, D.C., to become a reporter with WTOP News,[2] the news division of the radio and television stations owned by Washington Post-Newsweek. Although WTOP News was a local news department, it also covered national stories. At first Mudd did the 6:00 a.m. newscast for WTOP and he did local news segments on the local TV program Potomac Panorama.

During the fall of 1956, Mudd hosted the first newscast he wrote, WTOP's 6:00 p.m. newscast, that included a weekly commentary piece, all without "the constraints of the wire service vocabulary".[16] Mudd produced a half-hour TV documentary in summer 1957 advocating the need for a third airport in the Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan Area.

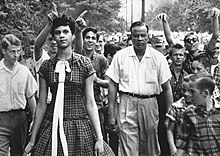

In September that year, Mudd conducted his first live TV studio interview. The interview was with Dorothy Counts, a black teenage girl who had suffered racial harassment at her otherwise all-white high school in Charlotte, North Carolina.[17] Then in March 1959 WTOP replaced Don Richards with Mudd for its 11 p.m. newscast.[18]

CBS News

[edit]CBS News was located on the third floor of WTOP's studios at 40th and Brandywine in northwest Washington, D.C. Mudd quickly came to the attention of CBS News and moved "downstairs" to join the Washington bureau on May 31, 1961.[19][3] For most of his career at CBS, Mudd was a Congressional correspondent. Mudd was also the anchor of the Saturday edition of CBS Evening News and frequently substituted on the weekday and weeknight broadcasts when regular anchormen Douglas Edwards and Walter Cronkite were on vacation or working on special assignments.[3] During the Civil Rights Movement, Mudd anchored the August 28, 1963, coverage of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom for CBS.[20]

On November 13, 1963, CBS-TV broadcast the documentary Case History of a Rumor, in which Mudd interviewed Rep. James Utt, a Republican of Santa Ana, California, about a rumor that Utt spread about Africans who were supposedly working with the United Nations to take over the United States.[21] Utt sued CBS-TV in U.S. Federal Court for libel, but the court dismissed the case.[22]

In 1964, Mudd became nationally known for covering the two-month filibuster of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, starting in late-March.[3]

Mudd also covered numerous political campaigns. He was paired with CBS journalist Robert Trout for the August 1964 Democratic National Convention anchor booth, temporarily displacing Walter Cronkite, in an unsuccessful attempt to match the popular NBC Chet Huntley–David Brinkley anchor team.[2] Mudd covered the 1968 Presidential campaign of United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy and interviewed him at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles only minutes before Kennedy was assassinated on June 5, 1968.[3]

Mudd hosted the seminal documentary The Selling of the Pentagon in 1971.[23] He won Emmys for covering the shooting of Gov. George Wallace of Alabama in 1972 and the resignation of Vice President Spiro T. Agnew in 1973, and two more for CBS specials on the Watergate scandal. In 1981,[24] he was a candidate to succeed Walter Cronkite as anchor of the CBS Evening News.[25] Despite substantial support for Mudd within the ranks of CBS News and an offer to co-host with Dan Rather, network management gave the position to Rather after the longtime White House and 60 Minutes correspondent threatened to leave the network for ABC News.[26]

Ted Kennedy interview

[edit]Mudd is best known for an interview with Senator Ted Kennedy broadcast on November 4, 1979.[24] The CBS Reports special Teddy, appeared three days before Kennedy announced his challenge to President Jimmy Carter for the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination. In addition to questioning Kennedy about the Chappaquiddick incident, Mudd asked, "Senator, why do you want to be President?" Kennedy's stammering answer, which has been described as "incoherent and repetitive"[27] and "vague, unprepared",[28] while the senator "twitched and squirmed" for an hour,[24] raised serious questions about his motivation in seeking the office, and marked the beginning of the sharp decline in Kennedy's poll numbers.[27]

Mudd described the reply as "almost a parody of a politician's answer".[29] Chris Whipple of Life, waiting to interview Kennedy, recalled being amazed by[30]

a hesitant, rambling and incoherent nonanswer; it seemed to go on forever without arriving anywhere. Mudd threw another softball, and Kennedy swung and missed again. On the simple question that would define him and his political destiny, Kennedy had no clue.

Carter defeated Kennedy for the nomination for a second presidential term.[2] Although the Kennedy family refused any further interviews by Mudd, the interview helped strengthen Mudd's reputation as a leading political journalist.[31]

Mudd won a Peabody Award for the interview.[24] He described as a "fantasy" Kennedy's statement in the latter's posthumous memoir, True Compass, that Mudd had asked for an interview to help him succeed Cronkite at CBS, and promised that he would not ask personal questions.[31] Mudd said "I don't think I should be known as the man who brought Teddy Kennedy down. I was the man who did an interview with him that was not helpful".[29] Whipple said that Mudd thought that the interview was a failure, and that Whipple had to assure him that Kennedy's incoherence would be a major story.[30] Broadcaster and blogger Hugh Hewitt and Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson have used the term "Roger Mudd moment" to describe a self-inflicted disastrous encounter with the press by a presidential candidate.[28]

NBC News

[edit]

In 1980, Mudd and Dan Rather were in contention to succeed Walter Cronkite as the weeknight anchor of the CBS Evening News. After CBS awarded the job to Rather (which he took over on March 9, 1981), Mudd chose to leave CBS News and he accepted an offer to join NBC News.[32] He co-anchored the NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw from April 1982 until September 1983, when Brokaw took over as sole anchor.[33]

From 1984 to 1985, Mudd was the co-moderator of the NBC Meet the Press program with Marvin Kalb, and later served as the co-anchor with Connie Chung on two NBC news magazines, American Almanac and 1986.[34]

PBS and The History Channel

[edit]From 1987 to 1993, Mudd was an essayist and political correspondent with the MacNeil–Lehrer Newshour on PBS. He was a visiting professor at Princeton University and Washington and Lee University from 1993 to 1996. Mudd was also a primary anchor for over ten years with The History Channel, where many of his programs are still repeated in reruns. Mudd retired from full-time broadcasting in 2004, and remained involved, until his death, with documentaries for The History Channel.[35][23]

Personal life

[edit]Mudd resided in McLean, Virginia. He was married to the former E. J. Spears of Richmond, Virginia, who died in 2011. They had three sons and a daughter: Daniel, the former CEO of Fortress Investment Group LLC and the former CEO of Fannie Mae;[36] the singer and songwriter Jonathan Mudd; the author Maria Mudd Ruth; and Matthew Mudd. He was survived by 14 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Mudd was a collateral descendant of Samuel Mudd (meaning he descended from another branch within the same extensive family tree), the doctor who was imprisoned for allegedly aiding and conspiring with John Wilkes Booth after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.[37]

Mudd was active as a trustee of the Virginia Foundation for Independent Colleges, with which he helped to establish its popular "Ethics Bowl", featuring student teams from Virginia's private colleges debating real-life cases involving ethical dilemmas.[38] He was also a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery.[7]

On December 10, 2010, he donated $4 million to his alma mater, Washington and Lee University, to establish the Roger Mudd Center for the Study of Professional Ethics and to endow a Roger Mudd Professorship in Ethics. "For 60 years," he said, "I've been waiting for a chance to acknowledge Washington and Lee's gifts to me. Given the state of ethics in our current culture, this seems a fitting time to endow a center for the study of ethics, and my university is its fitting home."[39]

Mudd died from complications of kidney failure at his home in McLean, Virginia, on March 9, 2021, at the age of 93.[40][24][41]

References

[edit]- Mudd, Roger (2008), The Place to Be: Washington, CBS, and the Glory Days of Television News, New York, New York, U.S.: PublicAffairs, ISBN 978-1-58648-576-4

Notes

[edit]- ^ Evans, Michael (1984). "Roger Mudd, National Portrait Gallery". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Roger Mudd, longtime network TV newsman, dies at 93". AP NEWS. March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Roger Mudd, probing TV journalist and network news anchor, dies at 93". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Mudd 2008, p. 19

- ^ Mudd 2008, p. 20

- ^ Bio, RogerMudd.com, 2008, archived from the original on July 25, 2009, retrieved July 17, 2009

- ^ a b "About Roger Mudd : Washington and Lee University". my.wlu.edu. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Famous Delts". Delta Tau Delta. n.d. Archived from the original on May 15, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ "Notable Members". Omicron Delta Kappa.

- ^ Mudd 2008, pp. 5–6

- ^ Mudd 2008, p. 8

- ^ Mudd, Roger (June 27, 2017). The Place to Be. PublicAffairs. ISBN 9781586486556.

- ^ Mudd 2008, pp. 11–12

- ^ Mudd 2008, p. 14

- ^ Mudd 2008, p. 16

- ^ Mudd 2008, pp. 20–21

- ^ Mudd 2008, p. 21

- ^ Mudd 2008, p. 23

- ^ Mudd 2008, pp. 30–32

- ^ Mudd 2008, pp. 116–117

- ^ Mudd 2008, pp. 122–124

- ^ Mudd 2008, pp. 124–125

- ^ a b "Roger Mudd, legendary CBS News reporter, has died at 93". news.yahoo.com. March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e McFadden, Robert D. (March 10, 2021). "Roger Mudd, Savvy Anchorman Who Stumped a Kennedy, Is Dead at 93". The New York Times. p. B11. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Al Eisele (April 19, 2008). "Roger Mudd's Revenge". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Martha Smilgis (March 3, 1980). "His Name Is Mud to CBS Rivals, but Dan Rather Says That's the Way It Is". People. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014.

- ^ a b Allis, Sam (February 18, 2009), Chapter 4: Sailing Into the Wind: Losing a quest for the top, finding a new freedom, The Boston Globe, retrieved March 10, 2009

- ^ a b Gerson, Michael (June 20, 2008), "A False Moderate?", The Washington Post, p. A19

- ^ a b The interview that blindsided the Ted Kennedy presidential campaign on YouTube

- ^ a b Whipple, Chris (August 28, 2009). "Ted Kennedy: The Day the Presidency Was Lost". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ a b Martin, Jonathan (September 18, 2009). "Roger Mudd: Ted Kennedy recollection a 'fantasy'". Politico.

- ^ "A new name's Mudd at NBC". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). UPI. July 5, 1980. p. 5, TV.

- ^ Frank, Reuven (1991). Out of Thin Air: The Brief Wonderful Life of Network News. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 383–84.

- ^ "Mudd Fumes Over NBC's Cancellation of His '1986' News Show". Chicago Tribune. December 11, 1986. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "Roger Mudd, longtime network TV newsman, dies at 93". Apnews.com. August 6, 2001. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Government may soon back troubled mortgage giants". Finance.comcast.net. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (May 25, 2002), "Dr. Richard Mudd, 101, Dies; Grandfather Treated Booth", The New York Times, retrieved May 23, 2009

- ^ HomeAdmin8T:16-05:00. "Virginia Foundation for Independent Colleges". VFIC. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Roger Mudd Center for Ethics : Washington and Lee University". Wlu.edu. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Roger Mudd: Veteran CBS newsman dies at 93 of kidney failure". USA Today. March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Roger Mudd, Veteran Newsman for CBS and NBC, Dies at 93". The Hollywood Reporter. March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

External links

[edit]- 1928 births

- 2021 deaths

- 20th-century American journalists

- American male journalists

- 21st-century American journalists

- 21st-century American memoirists

- American television news anchors

- American television reporters and correspondents

- CBS News people

- Deaths from kidney failure in the United States

- Journalists from Washington, D.C.

- Journalists from Virginia

- NBC News people

- Peabody Award winners

- Emmy Award winners

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill alumni

- Washington and Lee University alumni

- People from McLean, Virginia